Training for Speed - Developing Fast-Twitch Muscle Fibers

What Makes an Athlete 'Fast'

Have you ever noticed how some young athletes seem to always be a little bit quicker than their teammates? In most youth sports, coaches and parents can pick out the fastest or quickest athletes after only a few minutes of watching them play. What is the one thing that these athletes have in common? The ability to hit the ground hard and then drive their body in a specific direction! Stiff ankles, “twitchy” muscle contractions, and body awareness all play a role in an athlete’s ability to accelerate quickly. And no matter what sport they end up playing, the fast kids always have an advantage!

An athlete’s quickness, acceleration, and top end speed all depend on what is happening at ground contact. This is why some athletes are “stuck in the mud”, while some seam to run so fast it looks like they’re floating.

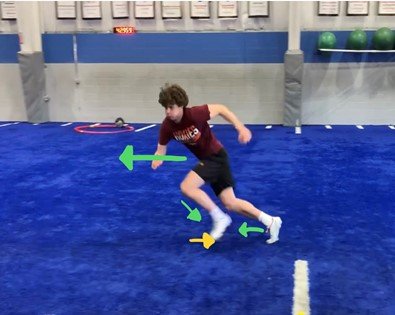

It boils down to Directional Force Production. As you can see in the picture below, linear acceleration requires an explosive move into a “forward knee” position, and then the athlete must drive back with their forward leg positioned in the opposite direction that they are accelerating.

The same concept applies when an athlete accelerates laterally. The key is to apply quick forces into the ground the opposite direction which you intend to move! The direction of an athlete’s shins dictate which direction the athlete moves (laterally or in a straight line). The shin angle is controlled by the hips (with internal rotation and external rotation).

All directional forces MUST pass through the ankle complex. This makes it well worth our time to improve our “ankle ability.” Poor ankle mobility and poor ankle strength is analogous to a car with poor suspension or shock absorbers.

Here are 3 simple things that can help any athlete get more out of their ankles and accelerate better:

1. Warm up barefoot

Running and moving barefoot builds neuro-control and strength in muscles that our shoes may prevent us from using.

2. Ankle wall-stretch paired with calf raises

Mobility without stability is likely to lead to ankle injuries, however flexibility is necessary to drive into the ground. Adding some active stretches pre-workout and passive stretches post-workout can help safely achieve ankle mobility.

3. Jump and land frequently and in different ways during training

Jumping increases ankle durability (strength at length), decrease reaction time at ground contact, and increases the ability to translate force production directionally through the ankle.

New to T3? What to learn more about speed? Email Info@t3athlete.com to set up a free athlete orientation session with one of our performance coaches.

Run Faster with a better foot strike

Run Faster with a better foot strike

When you are running, where do you strike the ground? And what part of the foot are you using?

In a previous post, we discussed how important dorsiflexion is to help an athlete get an extra step in their competition. Increasing our ankle's ability to manage ground collision can even be maximized with the proper part of the foot hitting the ground. It is important to remember that the laws of physics are in play when our athletes are trying to accelerate. With every action, there is going to be an equal and opposite reaction, so if I drive back to go forward, the athlete who drives down will go up!

This is most evident when we see athletes try and change directions or come out of an acceleration or drive phase by standing completely up! We sometimes use the coaching cue “say squatty” when working on acceleration.

We need to train our athletes to “hit and go” vs pound the ground. More specifically, hit the ground with a quick jab in the opposite direction they are trying to go. Make sure we strike keeping our heel off the ground.

The part of the foot that strikes the ground in acceleration can be called the “toe pad” or “ball of the foot” or more technically “the transverse arch of the foot.” This turns the foot into a lever system that helps continue an athlete’s acceleration, as opposed to a full foot strike, which can act as a breaking mechanism and slow an athlete down. An athlete trying to run fast but striking the ground with their heel first is like a car trying to accelerate with one foot on the gas pedal and the other foot on the break at the same time.

Here are three drills than can help an athlete strike the ground in the right direction and at the right angle.

1. Barefoot Sprinting. (20-60 yards)

a. This provides the athlete with automatic feedback on what part of their foot is hitting the ground.

2. Forward pogo jumps. (10 yards)

a. Coaching athletes to never let their heels touch during their reps

3. Bounding (10-30 yards)

a. Bounding helps develop proprioception at ground contact and increases the ankles ability to absorb and redirect forces similar to sprinting.

New to T3? What to learn more about speed? Email Info@t3athlete.com to set up a free athlete orientation session with one of our performance coaches.

Importance of Training with Plyometrics

The use of plyometric exercises in training can help foster athletic development in many ways. Different variations such as hurdle jumps, box jumps, lateral jumps, broad jumps, and squat jumps can be incorporated into training for variety. All of these jumps are athletic movements that build fast-twitch muscles and overall explosiveness. These fast-twitch muscle fibers directly translate into athletic performance. Jumps incorporate strong hip and knee extension which translates to most movements within athletics. The impact applied to joints when jumping promotes an increase in bone mineral content and collagen. Incorporating jumps into training can improve overall athleticism, strength, and movement quality.

Benefits of training jumps:

● Improve power

● Improve strength and build muscle

● Increase heart rate

● Injury prevention

● Coordination

● Muscle control

● Challenge hip extension and flexion

● Improved balance

● Speed development

● They are fun and competitive!

Jumps increase the rate of force production

The ability of an athlete to create and handle force is a key indicator of athletic potential. Jumps cause neurological adaptations which improve the rate of force development and improving landing mechanics increases an athlete’s ability to handle force and ground impacts. This can create direct carryover from jumps to squatting, deadlifts, sprinting, and overall athleticism.

Muscles Activated By Jumping

● Quadriceps: Quadriceps help propel athletes off of the ground while promoting knee extension. The Quadricep is activated for power when jumping and this helps promote speed and power.

● Hamstrings:Explosively activating the hamstrings when jumping improves lower body force production.

● Glutes: Support the hamstrings/quadriceps while creating hip extension that results from the glute. Jumps improve glute activation, which increases overall power.

● Calves: Responsible for ankle flexion, and are important for an athlete’s ability to be explosive, sprint, and jump high.

Different jump variations:

● Seated box jumps

● Jumps with weight

● 1-step box jump

● Single leg box jumps

● Broad jumps

● Squat jumps

● Lateral Jumps

● Vertical jumps

● Depth Drop to box jumps

● Running hurdle jumps

● 1-step hurdle jumps.

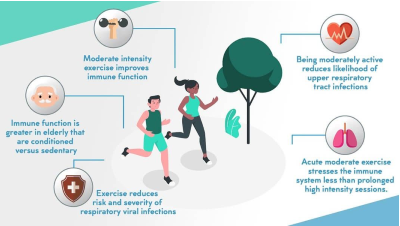

The Role of Exercise in Immune Function

Maintaining Lean Muscle Mass

A Lot of concerns around losing muscle mass during these times of quarantine. Here are a few strategies to help maintain your gains!

Eat a wholesome diet high in protein: Keep fueling your body with high quality food. It will help your body function properly and maintain a healthy status. Protein is your best friend when maintaining muscle mass. Eating 1.5-2.0 grams of protein per kg of body weight is a great general guideline. Here are some high protein foods you can eat:

Eggs

Lean meat (beef, poultry, seafood)

Beans

Greek yogurt

Protein shake (whey or plant based)

Continue to strength train with isometrics and eccentrics: Isometrics (holds) and eccentrics (control down phase) are great ways to make at home or body weight exercises more challenging. These types are more beneficial because they produce a greater rate of force development on the muscle fibers. Simply put, they challenge your body more! These can be done with or without equipment and are great for developing and maintaining strength and muscle mass.

Stay active: inactivity is the quickest way to lose muscle mass. Stay active with at home workouts, walking, and general physical activity. Sitting and laying down deloads your muscles causing atrophy.

Reducing Fatigue Through Active Recovery

Athlete Fatigue and The Overtraining Syndrome

At some point, all athletes experience fatigue. Under regular circumstances, an athlete will be fatigued after a tough practice or game, and they will recover within a few hours. During this recovery time, the muscular and cardiovascular systems adapt through improving efficiency of the heart, increasing capillaries in the muscles, and increasing glycogen stores and mitochondrial enzyme systems within the muscle cells. All of these adaptations result in a higher level of performance.

Coaches expect a lot out of their athletes, and sometimes two-a-days are unavoidable. Conditioning involves a combination of work overload and recovery, so you should expect to be tired after a few days of overload practices. However, when sufficient rest is not taken by an athlete, regeneration cannot occur. When insufficient rest periods continue (over a few weeks or more), performance will decline and overtraining syndrome may become present. Overtraining can be dangerous if it occurs. It takes a toll on the physical and mental health of the athlete, leading to a higher likelihood of injury and other issues.

Symptoms of Overtraining:

Feeling washed-out, tired, or drained for multiple consecutive days

Insomnia

Irritability

Headaches

Decreased Immunity (Getting sick more often)

Decreased training capacity (lowering intensity)

Depression

Decreased appetite

Causes of Stress and Fatigue

Inadequate rest periods (This includes sleep time and workout recovery time.)

Inadequate nutrition

Dehydration

Mental stress or anxiety

How to Combat Stress and Fatigue

1. Sleep

Get 8-9 hours of sleep each night. Your body needs this time to restore fuels and regenerate.

2. Drink Water

Dehydration will run you down very quickly. The average person needs about a half- gallon a day to stay fully hydrated. If you're working out and sweating often, you may need closer to a gallon of water a day.

3. Eat

Food supplies nutrients to your muscles and organs. Carbohydrates will give you energy to use. If you are working out for at least an hour a day, you should increase your caloric intake by 300-800 calories / day.

4. Allow your muscles to rest

When it comes to building muscle or athletic ability, more is not always better. Your muscles need to rest in order to regenerate. If you continually break them down without allowing 1-2 days of rest per week, your results will plateau and possibly decline.

5. Limit your stress

Make your goals attainable, rid yourself of negative influences, and don't take on too much. Mental stress can be just as exhausting as physical stress. Set your priorities and work on time management.